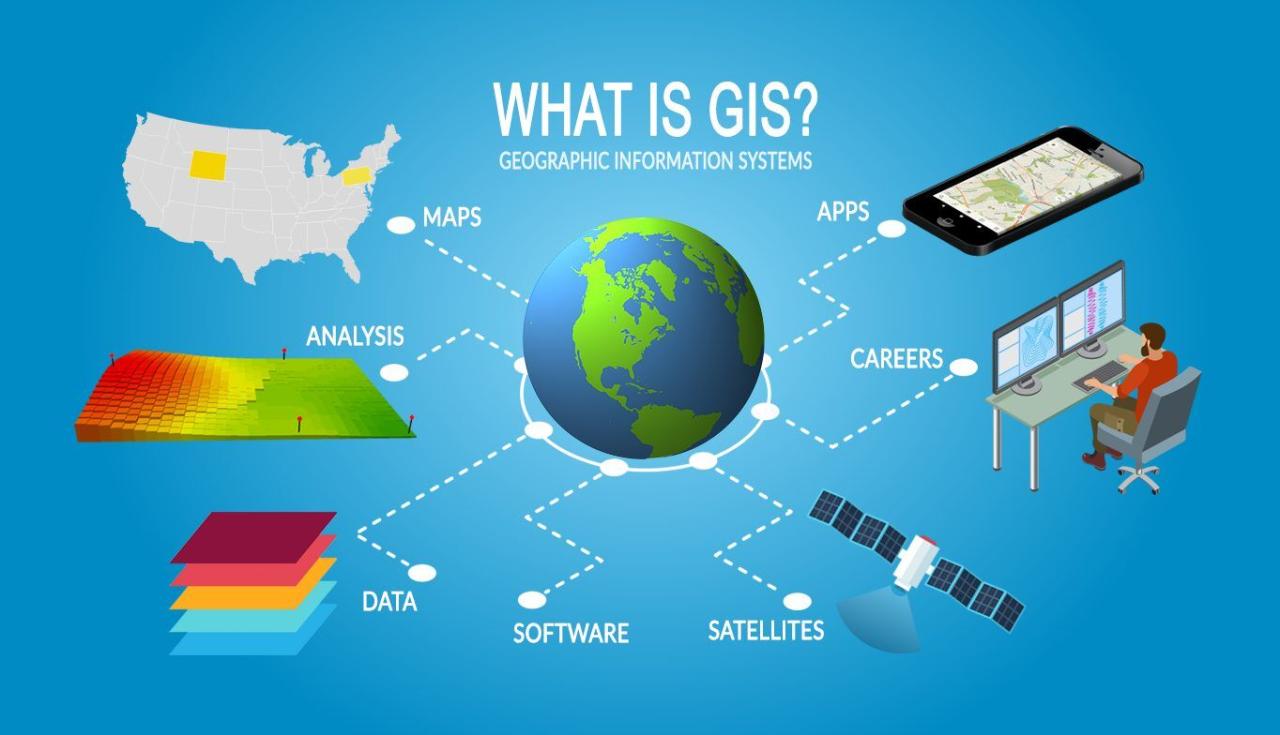

GIS software is revolutionizing how we interact with and understand our world. From mapping urban sprawl to tracking wildlife migration, GIS applications are incredibly diverse and powerful. This exploration delves into the core functionalities, data handling techniques, spatial analysis capabilities, and diverse applications of this transformative technology, covering everything from user interfaces to future trends.

We’ll examine various GIS software types—desktop, server, mobile, and cloud-based—highlighting their unique strengths and weaknesses. We’ll also cover data formats, import/export methods, and essential spatial analysis techniques like overlay analysis and buffer creation. The discussion will extend to map design, industry applications (urban planning, environmental management, transportation), cost considerations, security best practices, and emerging trends like AI integration and cloud computing’s impact.

Defining GIS Software

GIS software, or Geographic Information System software, is a powerful tool used to capture, store, manipulate, analyze, manage, and present all types of geographical data. Think of it as a supercharged map that’s far more than just pretty pictures; it’s a dynamic platform for understanding spatial relationships and solving real-world problems. It combines location data (where things are) with descriptive information (what things are) to create insightful visualizations and analyses.GIS software’s core functionalities revolve around the ability to input, process, and output geographic data.

GIS software is awesome for visualizing spatial data, but managing project finances can be a headache. Luckily, there are resources like free accounting software to help keep track of everything. This lets you focus on the cool GIS stuff, like analyzing patterns and making maps, without stressing about the budget. After all, good data visualization needs good financial management, too.

This includes tasks like creating and editing maps, performing spatial analysis (e.g., finding the nearest facilities, calculating distances, identifying overlaps), integrating data from various sources (e.g., satellite imagery, census data, GPS tracks), and presenting results in a variety of formats (e.g., maps, charts, reports). Essentially, it allows users to ask “what is where?” and then delve much deeper into “why is it there?” and “what does it mean?”.

Types of GIS Software

Different types of GIS software cater to various needs and user preferences. The choice often depends on factors such as the scale of the project, budget, technical expertise, and required functionalities.

- Desktop GIS: This is the traditional form of GIS software, installed on a single computer. It provides comprehensive functionalities and is suitable for individual users or small teams working on localized projects. Examples include ArcGIS Pro and QGIS.

- Server GIS: Designed for managing and sharing large datasets across networks, server GIS allows multiple users to access and work with the same geographic information simultaneously. This is ideal for organizations with extensive data and collaborative workflows. ArcGIS Enterprise and GeoServer are examples.

- Mobile GIS: Mobile GIS apps are designed for use on smartphones and tablets, enabling field data collection, real-time map viewing, and location-based services. These are often used for tasks such as asset management, environmental monitoring, and emergency response. Examples include Collector for ArcGIS and ArcGIS Field Maps.

- Cloud-based GIS: Cloud-based GIS leverages cloud computing infrastructure for data storage, processing, and sharing. This offers scalability, accessibility, and cost-effectiveness, especially for large-scale projects or organizations with geographically dispersed teams. Examples include ArcGIS Online and Google Earth Engine.

Examples of Common GIS Software Applications and Their Strengths

Several popular GIS software applications stand out for their specific strengths. Choosing the right software often hinges on the project’s requirements and the user’s technical expertise.

- ArcGIS Pro (Esri): A comprehensive desktop GIS offering a wide range of functionalities, strong analytical capabilities, and extensive customization options. It’s known for its user-friendly interface (relatively speaking) and vast community support, making it a popular choice for professionals.

- QGIS (Open Source): A free and open-source GIS software that offers surprisingly robust functionality, making it a cost-effective option for individuals, students, and organizations with limited budgets. While it may have a steeper learning curve than ArcGIS Pro, its active community provides ample support and resources.

- Google Earth Engine: A cloud-based platform ideal for large-scale geospatial analysis, particularly using satellite imagery and other massive datasets. Its power lies in its ability to process vast amounts of data quickly and efficiently, making it suitable for research and environmental monitoring on a global scale. Its ease of use for some tasks is offset by a steeper learning curve for advanced functions.

Data Handling in GIS Software

GIS software’s power lies not just in its analytical capabilities, but also in its ability to effectively manage vast amounts of geospatial data. This data comes in diverse formats, requiring understanding of import/export methods and robust data management techniques for efficient analysis and visualization. Think of it like organizing a massive library – without a good system, finding what you need becomes a nightmare.Data formats in GIS are incredibly varied, each with its own strengths and weaknesses.

Understanding these differences is crucial for selecting the right format for your project and ensuring seamless data exchange.

Geospatial Data Formats

GIS software utilizes a variety of data formats to represent geographic information. Raster data, like satellite imagery or scanned maps, represents data as a grid of cells, each with a value. Vector data, on the other hand, represents data as points, lines, and polygons, ideal for representing discrete features like roads or buildings. Common raster formats include GeoTIFF (.tif), JPEG (.jpg), and ERDAS Imagine (.img).

Popular vector formats include Shapefiles (.shp), GeoJSON (.geojson), and File Geodatabase (.gdb). Each format has its own specifications regarding data storage and metadata, influencing the choice depending on the project’s needs and the software being used. For example, GeoTIFF is widely supported and includes georeferencing information, while Shapefiles, though widely used, are limited in their ability to handle complex attributes.

Importing and Exporting Geospatial Data

Moving data between different GIS software packages or transferring data from other sources is a common task. Most GIS software provides tools for importing various data formats. For example, you can directly import shapefiles, GeoTIFFs, and CSV files containing geographic coordinates. Exporting data is equally important, allowing for sharing of results or integration with other systems. Common export formats mirror the import options, allowing for flexibility in data exchange.

The process often involves selecting the desired output format and specifying the projection and coordinate system. For instance, exporting a layer as a shapefile allows for easy use in other GIS applications or for sharing with colleagues who may not have access to your specific software. Exporting to a GeoJSON format allows for easy integration with web mapping applications.

Data Management Techniques in GIS

Effective data management is essential for maintaining data integrity and ensuring efficient workflow. This involves establishing clear naming conventions for files and folders, implementing a robust metadata system to document data sources and attributes, and regularly backing up data to prevent loss. Data cleaning and validation are also critical steps to ensure data accuracy and consistency. This may involve checking for inconsistencies in attribute data or identifying spatial errors.

Techniques like geoprocessing tools can automate many data management tasks, such as creating buffers or clipping features, streamlining the workflow. For example, a regular backup schedule and a well-defined folder structure will prevent accidental data loss and ensure easy retrieval of specific datasets. Using consistent attribute names and data types across different layers promotes data integration and simplifies analysis.

Spatial Analysis with GIS Software

Spatial analysis is where GIS really shines. It’s the process of manipulating spatial data to extract meaningful information and answer complex questions about geographic patterns and relationships. Think about analyzing crime hotspots, predicting the spread of disease, or optimizing delivery routes – these are all tasks perfectly suited for GIS’s spatial analysis capabilities. We’ll explore this fascinating area by examining a typical workflow and some key techniques.

A typical spatial analysis workflow involves several steps: defining the problem and objectives, selecting appropriate data, performing the analysis using specific tools, interpreting the results, and communicating findings. The specific tools and techniques used will vary depending on the software and the nature of the analysis. Let’s use ArcGIS Pro as an example to walk through a common workflow.

ArcGIS Pro Workflow for Spatial Analysis

A common workflow in ArcGIS Pro might involve importing data layers (like roads, land use, and population density), performing overlay analysis to identify areas where multiple criteria overlap (for example, finding suitable locations for a new park based on proximity to residential areas and green space), creating buffers around points or lines to define areas of influence (such as determining the area affected by a natural disaster), and finally visualizing and interpreting the results using maps and charts.

This process allows for the identification of spatial patterns and relationships that would be difficult or impossible to discern manually.

Overlay Analysis

Overlay analysis combines two or more spatial layers to create a new layer that contains information from both. For instance, imagine you have a layer showing areas suitable for agriculture and another showing areas with high biodiversity. Performing an overlay analysis (like an intersect) would reveal areas that are both suitable for agriculture and have high biodiversity, helping to identify locations for sustainable farming practices.

The specific overlay method (intersect, union, erase, etc.) depends on the research question and the desired outcome. The result would be a new layer showing only the areas where both the agricultural suitability and high biodiversity layers overlap. This allows for a more nuanced understanding of the land’s potential for both agriculture and conservation.

Buffer Creation

Buffering is a fundamental spatial analysis technique that creates zones around geographic features. For example, creating a 1-kilometer buffer around a river would identify all areas within 1 kilometer of the river. This could be useful for identifying areas at risk of flooding or for analyzing the impact of river proximity on land use patterns. Buffers can be created around points, lines, or polygons, and the buffer distance can be adjusted based on the specific application.

For instance, a larger buffer might be created around a hazardous waste site to ensure a wider safety zone. In contrast, a smaller buffer might be sufficient around a bus stop to assess pedestrian accessibility.

Common Spatial Analysis Techniques and Their Applications

Beyond overlay analysis and buffering, many other spatial analysis techniques exist, each with specific applications. Understanding the strengths and limitations of each technique is crucial for effective spatial analysis.

| Technique | Description | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Proximity Analysis | Measures the distance between spatial features. | Identifying nearest hospitals, assessing accessibility to services. |

| Density Analysis | Calculates the density of points or features within a given area. | Identifying crime hotspots, analyzing population distribution. |

| Spatial Interpolation | Estimates values at unsampled locations based on known values. | Predicting rainfall patterns, creating elevation models. |

| Network Analysis | Analyzes spatial relationships along networks (roads, rivers). | Optimizing delivery routes, assessing accessibility. |

GIS Software User Interface and Functionality

GIS software interfaces, while all aiming to achieve similar spatial data manipulation, vary significantly in their approach to user experience. This leads to differences in workflow efficiency and the overall user’s comfort level. Understanding these differences is key to selecting the appropriate software for a specific project or skillset. We’ll explore the user interfaces of three popular GIS packages, outlining their strengths and weaknesses.

The functionality of GIS software is vast, encompassing data input, manipulation, analysis, and visualization. Effective use relies on understanding the tools available and how to integrate them into a coherent workflow. A step-by-step guide will demonstrate a common task, and a list of common tools will clarify their respective functions.

Comparison of User Interfaces: QGIS, ArcGIS Pro, and Google Earth Engine

QGIS, ArcGIS Pro, and Google Earth Engine represent different approaches to GIS software design. QGIS, an open-source option, prioritizes flexibility and customization, offering a modular interface that can be tailored to individual preferences. Its interface can feel initially less intuitive than commercial counterparts but provides extensive control over functionality. ArcGIS Pro, a commercial package, emphasizes a streamlined, ribbon-based interface similar to Microsoft Office applications.

This familiar design makes it relatively easy to learn, but its extensive features can sometimes feel overwhelming. Google Earth Engine, a cloud-based platform, provides a unique web-based interface focused on big data processing and analysis. Its interface is very different from desktop-based GIS software, relying heavily on scripting and code for advanced operations. The visual interface is streamlined for efficient exploration of large datasets.

Step-by-Step Guide: Buffer Creation in QGIS

This guide demonstrates creating a buffer around a point layer in QGIS. This is a fundamental spatial analysis operation used to define areas of influence around geographic features.

- Load the Point Layer: Navigate to Layer > Add Layer > Add Vector Layer. Select your point shapefile and click Add.

- Access the Buffer Tool: Go to Processing Toolbox (usually found in the lower left panel). Search for “Buffer” and select the “Fixed distance buffer” tool.

- Configure the Buffer Parameters: In the tool’s dialog box, select your point layer as the input layer. Specify the buffer distance (e.g., 100 meters) and the desired output layer settings (file name, location, etc.).

- Run the Tool: Click Run. QGIS will process the data and create a new polygon layer representing the buffers around your points.

- Visualize the Results: The newly created buffer layer will be added to your map canvas. You can style it to improve visual clarity.

Common GIS Software Tools and Their Functions

Understanding the function of common GIS tools is crucial for efficient spatial analysis. The following table lists some essential tools and their applications.

| Tool | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Buffer | Creates zones around features. | Determining areas within a certain distance of a river. |

| Clip | Extracts the portion of a layer that intersects with another. | Selecting only the parts of a road network that fall within a specific county boundary. |

| Intersect | Identifies the overlapping areas between layers. | Finding areas where land use overlaps with floodplains. |

| Union | Combines multiple layers into a single layer. | Merging different land cover types into a single comprehensive layer. |

| Spatial Join | Adds attributes from one layer to another based on spatial relationships. | Adding population data to a polygon layer representing census tracts. |

Mapping and Visualization in GIS Software

GIS software offers powerful tools for creating compelling and informative maps, transforming raw spatial data into visually engaging representations. The process involves selecting appropriate data, choosing suitable map types, and applying design principles to enhance clarity and understanding. Effective visualization is key to communicating spatial patterns and relationships effectively.

Creating thematic maps in GIS software is a multi-step process. First, you need to define the purpose of your map—what story are you trying to tell? This dictates your data selection. Next, you’ll import your data into the GIS software, ensuring it’s properly georeferenced and projected. Then, you select a suitable map type (choropleth, dot density, proportional symbol, etc.) depending on the nature of your data and the message you want to convey.

Finally, you symbolize your data, add labels and a legend, and refine the overall design for maximum impact.

Thematic Map Creation Process

The process of creating a thematic map typically involves these key steps: data selection and preparation; choosing an appropriate map type; symbolizing the data; adding labels and a legend; and refining the map design. For instance, to create a map showing population density across a state, you would first gather population data for each county, import it into the GIS software, then choose a choropleth map to represent population density using color gradients.

The color scheme should be carefully chosen for clarity and to avoid misleading interpretations. Data outliers should be considered and handled appropriately, perhaps by using a graduated symbol map instead of a choropleth map if the variation is extreme.

Techniques for Improving Map Readability and Visual Appeal

Effective map design is crucial for conveying information clearly and engagingly. Several techniques can significantly improve readability and visual appeal. These include careful selection of colors and symbology, appropriate use of labels and a clear legend, and the application of cartographic principles such as figure-ground contrast and visual hierarchy.

Examples of Effective Map Design Principles

Consider a map depicting air quality index (AQI) values across a city. A well-designed map might use a graduated color scheme (e.g., green for good AQI, red for hazardous AQI) to represent AQI levels. Clear labels for major roads and neighborhoods would enhance orientation. A well-placed legend clearly explains the color-AQI relationship. The map background should be simple and not compete with the data being presented.

Using a consistent font and size for labels ensures readability. The use of a visually appealing color palette (e.g., avoiding clashing colors) enhances the overall aesthetic appeal without sacrificing clarity.

Data Classification Methods for Thematic Mapping

The way data is classified significantly impacts the visual representation and interpretation of a thematic map. Several methods exist, each with strengths and weaknesses. For example, equal interval classification divides the data range into equal intervals, while quantile classification assigns an equal number of data points to each class. Natural breaks classification identifies clusters in the data to define class boundaries.

The choice of classification method should depend on the data distribution and the intended message of the map.

GIS Software Applications in Different Industries

GIS software has become an indispensable tool across numerous sectors, offering powerful capabilities for spatial data management, analysis, and visualization. Its applications extend far beyond simple map-making, impacting decision-making processes and operational efficiencies in diverse fields. This section explores some key examples of GIS software’s impact on urban planning, environmental management, and transportation.

GIS in Urban Planning

Urban planners utilize GIS software extensively for a wide range of tasks, from infrastructure planning to analyzing population density and demographics. GIS allows for the overlaying of various datasets, such as zoning regulations, transportation networks, and environmental data, to create comprehensive models of urban areas. This integrated approach enables planners to identify optimal locations for new developments, assess the impact of proposed projects on existing infrastructure and the environment, and develop more sustainable and resilient urban environments.

For instance, a city might use GIS to model the impact of a new highway on traffic flow, air quality, and surrounding neighborhoods, allowing for informed decisions about routing and mitigation strategies. The ability to visualize and analyze spatial relationships is crucial for effective urban planning and the creation of livable, functional cities.

GIS in Environmental Management

Environmental management relies heavily on the capabilities of GIS software to monitor and analyze environmental conditions. GIS enables the visualization and analysis of spatial data related to pollution levels, deforestation, wildlife habitats, and climate change impacts. This allows environmental scientists and managers to identify areas at risk, track changes over time, and develop targeted conservation and mitigation strategies.

For example, a conservation organization might use GIS to map the distribution of an endangered species, identify suitable habitat corridors, and plan for effective conservation efforts. Similarly, GIS can be used to model the spread of wildfires or the impact of sea-level rise, providing valuable insights for disaster preparedness and mitigation. The ability to integrate various environmental datasets, from satellite imagery to ground-based measurements, provides a comprehensive understanding of environmental challenges and supports evidence-based decision-making.

GIS in the Transportation Sector

The transportation sector benefits significantly from the use of GIS software in various aspects of planning, management, and operations. GIS helps optimize route planning, manage fleets, and analyze traffic patterns. Transportation planners use GIS to design efficient road networks, optimize public transportation routes, and assess the impact of transportation infrastructure projects on traffic flow and accessibility. For example, a transportation authority might use GIS to model the impact of a new light rail line on commute times, reducing congestion and improving public transit access.

Furthermore, GIS can be used to track the location of vehicles in real-time, manage logistics and delivery routes, and improve safety and efficiency across the transportation network. The integration of real-time data with GIS allows for dynamic routing and informed decision-making, enhancing the overall effectiveness and efficiency of transportation systems.

Cost and Licensing of GIS Software

Choosing the right GIS software often involves a careful consideration of cost and licensing. The pricing models vary significantly, impacting both initial investment and long-term expenses. Understanding these models is crucial for organizations and individuals alike to make informed decisions based on their specific needs and budgets.The licensing agreements themselves can be complex, covering aspects like permitted usage, permitted number of users, and geographical restrictions.

This section will delve into the pricing and licensing details of several popular GIS software packages, offering a comparative overview to aid in decision-making.

Pricing Models of GIS Software

GIS software vendors typically employ a variety of pricing models. These models often reflect the scale of the software, the level of support provided, and the intended user base. Common models include perpetual licensing, subscription-based licensing, and tiered pricing structures based on functionality and user numbers. Perpetual licenses involve a one-time purchase, granting permanent usage rights, while subscription models involve recurring annual or monthly fees for continued access and support.

Tiered pricing allows users to select packages that best suit their needs and budget, offering various levels of functionality and user capacity at different price points. For example, a small business might opt for a basic subscription, while a large corporation might invest in a comprehensive, multi-user perpetual license with premium support.

Licensing Agreements and Terms of Use

Licensing agreements for GIS software detail the permitted use of the software. These agreements typically cover the number of users allowed, geographical limitations on usage, and restrictions on redistribution or modification of the software. Violation of these terms can result in legal action. Popular software packages like ArcGIS, QGIS, and MapInfo Pro all have their own specific licensing terms that users must carefully review before purchasing or using the software.

Many agreements also include clauses related to data ownership, intellectual property rights, and liability. It’s vital to understand these terms to avoid future complications and ensure compliance.

Comparison of GIS Software Packages

The following table compares three popular GIS software packages: ArcGIS Pro, QGIS, and MapInfo Pro. The comparison focuses on key features, pricing models, and licensing terms to provide a concise overview for potential users. Note that pricing can vary depending on specific configurations and support levels.

| Feature | ArcGIS Pro | QGIS | MapInfo Pro |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pricing Model | Subscription or Perpetual | Free, Open Source | Subscription or Perpetual |

| Licensing | ESRI’s End-User License Agreement (EULA) | GNU General Public License | Pitney Bowes’ EULA |

| Spatial Analysis Capabilities | Extensive, including advanced geostatistics and 3D analysis | Robust, with a wide range of tools and extensions | Comprehensive, with strong support for network analysis |

| Data Formats Supported | Wide range, including proprietary and open formats | Many open formats, plus support for proprietary formats through plugins | Strong support for various vector and raster formats |

| User Interface | Intuitive, but can have a steep learning curve for beginners | Can be less intuitive initially, but highly customizable | User-friendly interface, relatively easy to learn |

| Typical Cost (USD) | Varies greatly depending on the license type and number of users; can range from hundreds to thousands per year or a one-time purchase of several thousand dollars. | Free | Varies greatly depending on the license type and number of users; can range from hundreds to thousands per year or a one-time purchase of several thousand dollars. |

GIS Software and Data Security

Geospatial data is incredibly valuable, often containing sensitive information about individuals, infrastructure, and environments. Because of this, securing this data within a GIS environment is paramount. Failure to do so can lead to significant financial losses, reputational damage, and legal repercussions. This section will explore best practices, privacy considerations, and potential security risks associated with GIS data management.Protecting geospatial data requires a multi-layered approach.

It’s not just about the software itself, but also about the people who use it and the processes involved in handling the data. Think of it like a fortress – you need strong walls, vigilant guards, and secure internal systems.

Best Practices for Securing Geospatial Data

Implementing robust security measures is crucial for protecting geospatial data. This involves a combination of technical, administrative, and physical controls. Technical controls might include encryption of data both at rest and in transit, access control lists restricting who can view or modify specific data, and regular security audits to identify vulnerabilities. Administrative controls would include establishing clear data governance policies, providing regular security awareness training for staff, and implementing robust incident response plans.

Physical controls might involve secure storage of physical media containing geospatial data and limiting access to server rooms. A layered approach ensures that even if one security measure fails, others are in place to mitigate the risk.

Data Privacy Considerations When Using GIS Software

Privacy is a major concern when working with geospatial data, especially when it includes personally identifiable information (PII). GIS data often pinpoints locations with incredible accuracy, making it possible to identify individuals or organizations if not properly anonymized or aggregated. Compliance with regulations like GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) and CCPA (California Consumer Privacy Act) is critical. Data minimization, which involves collecting and storing only the data necessary for a specific purpose, is a key principle.

Pseudonymization, replacing identifying information with pseudonyms, and anonymization, removing all identifying information, are also important techniques to protect individual privacy. Consider the implications of your data – could it be used to identify individuals? If so, strong privacy protections are necessary.

Potential Security Risks Associated with GIS Data Management

Several security risks are associated with GIS data management. Unauthorized access, whether through hacking or insider threats, is a major concern. Data breaches can lead to the exposure of sensitive information, resulting in financial losses, legal liabilities, and reputational damage. Malicious attacks, such as data manipulation or denial-of-service attacks, can disrupt operations and compromise data integrity. Another significant risk is the accidental loss or deletion of data due to human error or system failures.

Regular backups and disaster recovery plans are essential to mitigate this risk. Finally, weak security configurations within the GIS software itself can create vulnerabilities that malicious actors can exploit. Keeping the software updated with the latest security patches is vital to prevent these exploits.

Future Trends in GIS Software

The field of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) is constantly evolving, driven by advancements in computing power, data availability, and analytical techniques. The future of GIS software promises even more powerful tools and capabilities, fundamentally changing how we interact with and understand our world. This section will explore some of the key trends shaping the future of GIS.

Cloud Computing’s Impact on GIS Software Development

Cloud computing is revolutionizing GIS software development by offering scalable, cost-effective, and collaborative platforms. Instead of relying on expensive, on-premise servers, GIS software and data can be hosted in the cloud, accessible from anywhere with an internet connection. This allows for easier collaboration among users, reduced infrastructure costs for organizations, and improved data management through centralized storage and access control.

Major GIS vendors are increasingly offering cloud-based solutions, integrating their software with cloud platforms like Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Microsoft Azure. This allows for seamless integration with other cloud-based services and tools, fostering a more interconnected and efficient workflow for GIS professionals. For example, a team of urban planners working on a city-wide infrastructure project can access and share the same GIS data and software tools from different locations simultaneously, greatly accelerating the project’s progress.

The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Advancing GIS Capabilities, Gis software

Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly transforming GIS capabilities, particularly in areas like automated feature extraction, predictive modeling, and real-time analysis. AI algorithms, including machine learning and deep learning, can analyze vast amounts of geospatial data to identify patterns, make predictions, and automate tasks that previously required significant manual effort. For instance, AI can be used to automatically identify buildings and roads from satellite imagery, significantly speeding up the process of map creation and updating.

Predictive modeling using AI can forecast things like traffic flow, crime hotspots, or the spread of diseases, allowing for proactive interventions. Real-time analysis using AI can process sensor data from various sources (e.g., GPS trackers, IoT devices) to provide up-to-the-minute information on dynamic events, such as traffic congestion or environmental hazards. The integration of AI and GIS is creating a new generation of intelligent geospatial systems capable of providing more accurate, timely, and insightful information.

Emerging Trends in Geospatial Data Visualization and Analysis

Geospatial data visualization is evolving beyond traditional maps and charts. New techniques are emerging that offer more immersive and interactive experiences, making complex geospatial data easier to understand and interpret. These include 3D visualization, virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR) applications, and the use of interactive dashboards and storytelling tools. 3D visualization allows users to explore geospatial data in a three-dimensional space, providing a more realistic and intuitive understanding of the data.

VR/AR applications allow users to immerse themselves in geospatial data, experiencing it in a more engaging and interactive way. Interactive dashboards and storytelling tools provide a more user-friendly way to present and share geospatial insights, making complex information accessible to a wider audience. For example, a 3D model of a city could overlay environmental data to illustrate pollution levels, while an interactive dashboard could display real-time traffic conditions.

These advancements are enhancing the communication and accessibility of geospatial insights, leading to better informed decision-making across various fields.

Troubleshooting Common GIS Software Issues

GIS software, while powerful, can sometimes throw curveballs. Understanding common problems and their solutions is key to maximizing efficiency and avoiding frustrating delays. This section covers troubleshooting strategies for data import/export, performance optimization, and other typical hiccups.

Data Import/Export Problems

Data import and export are frequent tasks in GIS workflows, and inconsistencies can quickly derail a project. Issues often stem from file format incompatibility, incorrect projection definitions, or corrupted data. Addressing these requires careful attention to detail and a systematic approach.

One common problem is importing data in the wrong projection. If the projection of the imported data doesn’t match the project’s coordinate system, features will be geographically misplaced. The solution involves defining the correct projection during the import process, often by specifying the appropriate coordinate system parameters (e.g., EPSG code). Another frequent issue is data corruption. This could manifest as missing attributes, distorted geometries, or completely unusable files.

In such cases, checking the source data for errors, or trying a different import method (e.g., using a different file format or software) is essential. Sometimes, data cleaning might be necessary before importing to correct errors in the source data itself.

Performance Optimization Techniques

Slow processing speeds are a common complaint with GIS software, particularly when dealing with large datasets. Several strategies can be employed to boost performance.

One effective approach is to simplify complex geometries. High-resolution data with many vertices can significantly impact processing times. Generalizing geometries by reducing the number of vertices can improve performance without substantial loss of detail in many cases. For instance, a highly detailed coastline could be simplified to a smoother line without losing its overall shape. Another key technique involves using appropriate data structures.

Spatial indexes, such as R-trees or quadtrees, can dramatically speed up spatial queries by organizing data efficiently. Finally, optimizing hardware can also make a significant difference. Using a computer with sufficient RAM, a fast processor, and a solid-state drive (SSD) will greatly enhance software performance.

Resolving Common Errors

Various error messages can pop up during GIS software use. Understanding the underlying causes and implementing appropriate solutions is crucial.

For example, an error related to insufficient memory often indicates that the software is attempting to process more data than the system’s available RAM can handle. Solutions include closing unnecessary applications, increasing the available RAM (if possible), or processing data in smaller chunks. Another common issue is file path errors, often caused by incorrect file references or missing data files.

Carefully checking file paths and ensuring all necessary files are accessible will usually resolve this problem. A systematic approach, involving careful review of error messages and the documentation of the software, is vital in efficiently addressing a wide variety of error conditions.

Extending GIS Software Functionality with Extensions and Plugins

GIS software, while powerful out-of-the-box, often benefits from extensions and plugins that add specialized tools and functionalities. These add-ons allow users to tailor their software to specific needs and workflows, boosting efficiency and expanding analytical capabilities beyond the core program’s features. Think of them as app stores for your GIS software, offering a vast library of enhancements.Extending GIS software functionality through extensions and plugins involves installing and configuring these add-ons, then leveraging their capabilities within the main GIS application.

This process typically involves downloading the extension from a trusted repository, following the software’s installation instructions, and then activating the plugin within the GIS software’s settings or interface. The specific steps will vary depending on the software (e.g., ArcGIS Pro, QGIS) and the extension itself.

Popular Extensions and Their Functionalities

Many popular extensions enhance GIS software’s capabilities significantly. For example, in ArcGIS Pro, the “Spatial Analyst” extension provides advanced spatial analysis tools like surface analysis and hydrological modeling, allowing for sophisticated terrain analysis and prediction of water flow. Another example is the “3D Analyst” extension, which enables the creation and manipulation of 3D GIS data, facilitating visualizations of terrain and urban environments.

In QGIS, the “Processing Toolbox” plugin offers a wide range of geoprocessing algorithms, providing functionality similar to ArcGIS Spatial Analyst but within a free and open-source environment. These extensions greatly expand the analytical power of the base software, enabling users to perform complex tasks that would otherwise be difficult or impossible.

Integrating External Data Sources with Plugins

Plugins often play a crucial role in integrating external data sources into GIS software. This is particularly important when working with data formats not natively supported by the core software or when needing to connect to external databases. For instance, a plugin might allow for seamless integration with a remote sensing data repository, enabling the direct download and processing of satellite imagery.

Another example could be a plugin facilitating connections to databases like PostgreSQL/PostGIS, enabling users to query and visualize spatial data directly from a relational database. These plugins act as bridges, connecting the GIS software to a wider range of data sources, greatly enhancing its data management and analytical capabilities. Effective integration is critical for a comprehensive GIS workflow.

Concluding Remarks

Ultimately, GIS software empowers us to visualize, analyze, and interpret geospatial data with unprecedented precision. From urban planning to environmental conservation, the applications are limitless. Understanding its capabilities, limitations, and security implications is crucial for leveraging its full potential. As technology continues to evolve, GIS will undoubtedly play an even more significant role in shaping our future. So buckle up, and let’s explore the fascinating world of geographic information systems!

Quick FAQs: Gis Software

What’s the difference between vector and raster data?

Vector data represents geographic features as points, lines, and polygons (think city boundaries, roads, buildings). Raster data uses a grid of cells to represent geographic features (think satellite imagery, elevation models).

Is GIS software expensive?

It varies widely. Some open-source options are free, while others have hefty price tags depending on features and licensing. There are also cloud-based options with subscription models.

How can I learn GIS software?

Many online courses, tutorials, and university programs offer GIS training. Start with the basics, then focus on specific software and applications relevant to your interests.

What are some common GIS software errors?

Data projection issues, file format incompatibility, and corrupted data are common problems. Troubleshooting often involves checking data integrity and ensuring consistent projections.

What kind of career paths use GIS?

GIS professionals work in diverse fields like urban planning, environmental science, transportation, public health, and even archaeology. Roles range from GIS analysts and technicians to managers and researchers.